The Electric Waffle-Maker Acid Test

Too little sugar made my waffles “biscuit-y,” but just enough meant they got too dark—almost burnt. A better waffle maker would help, sure, but so too can science.

The (non-enzymatic) browning of food happens by way of two processes: the Maillard reaction and caramelization. Adding proteins to break down to aminos for the former and sugar for the latter will both lead to food browning. Acidity impacts the two reactions differently.

When you nudge food’s pH toward acidic, the Maillard reaction happens more slowly; when you nudge it toward alkaline, it happens more quickly. For example, a pinch of baking soda is gonna speed up the process of browning onions in a surprisingly dramatic way. In the case of caramelization, pH-neutral is going to give you the least browning—increasing acidity or alkalinity are going to mean darker food, faster.

Both processes were taking place in my waffle recipe (in fact, both are pretty much always taking place when you apply heat to food), but I don’t think they’re happening in equal measure. Our man Maillard is involved, sure: flour, eggs, and the milk solids in the butter are all in his turf when it comes to browning. But there are a lot of sugars in those things, meaning loads of caramelization taking place at the same time. Enough sugar to prevent these from tasting like weirdly-shaped bread was enough that the outside seemed almost burnt.

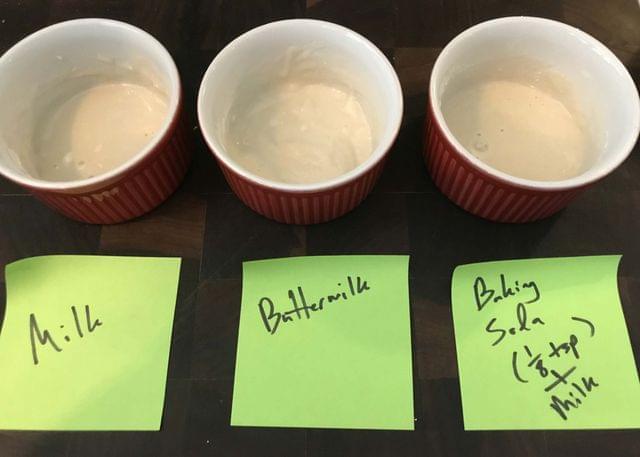

My first attempts used milk as the liquid, which is pretty typical of liège waffles—milk is pH neutral, give or take a hint of lactic acid. Buttermilk is acidic. Baking soda is alkaline.

Now, I’m no scientist—the previous section is more or less the extent of my knowledge on this subject. I don’t know the extent to which acidity impacts Maillard browning vs. caramelization. I do know:

- I can’t really slow down caramelization, I don’t think?

- I can slow down Maillard browning by adding acid.

- The mechanism by which I slow down Maillard browning might speed up caramelization, but I don’t know the extent.

So, I put together some test cases: three experiments, each alike in dignity, using a 50/50 mix of all-purpose flour and confectioners' sugar—one tablespoon each. Into them, I added: 1 tablespoon of whole milk, 1 tablespoon of buttermilk, and 1 tablespoon of whole milk plus 1/8 teaspoon of baking soda.

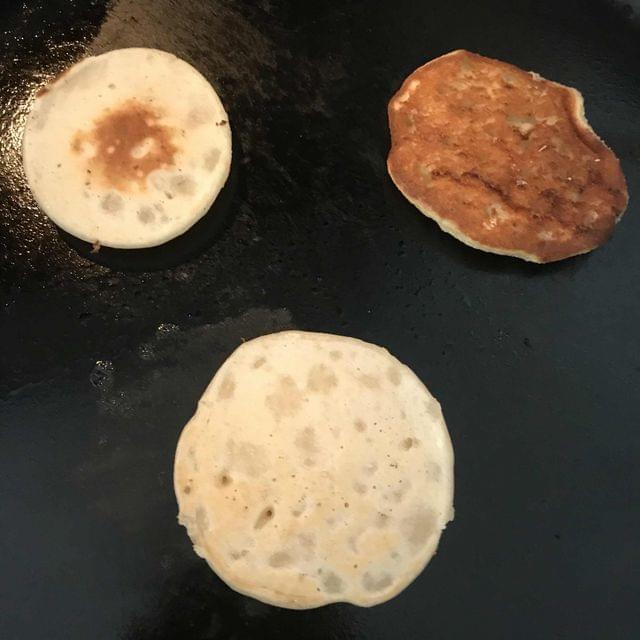

I spooned each into a cast-iron skillet that had spent ten or so minutes over low heat (so it would heat up as evenly as a home burner will allow). After five minutes or so, I flipped them in the order in which I’d spooned them out, so the cook time was as close-as-in-horseshoes to identical all around.

Predictably enough, the alkaline “pancake” turned a deep, even brown. That’s a lot of baking soda in a tiny spoonful of batter; that’s to be expected. I tasted it, I don’t mind admitting, and baking soda’s tell-tale soapy flavor was… pronounced. The test case using milk had started to brown in the center, where the first of the batter had made contact with the pan; a few more minutes and it would’ve been brown throughout. The test case using buttermilk was still ghostly pale.

What does this say? Well, my best guess is that buttermilk isn’t acidic enough to have an impact on the rate of caramelization, but is acidic enough to have an impact on Maillard-style browning. So, one final test: two more tiny batches of similar batter—one tablespoon of AP flour, and one tablespoon of powdered sugar, each. Into one, one tablespoon plus one teaspoon of milk—in the other, one tablespoon of milk plus one teaspoon of lemon juice.

The lemon juice had a big impact on consistency, which is to be expected—the acid caused the milk to curdle and thicken. That batch also stayed pale long after the batch with just flour, sugar, and milk had started to brown. Even with a lot more acid in play, we end up with similar results: more acid means less browning, even when there’s a ton of sugar in the literal and figurative mix.

So, is there a point where acidity will make caramelization happen much more quickly? I mean, probably—I don’t know how much it would take, though. Look at it this way: if a lemon tart can stay pale and golden despite a hell of a lot of acid and eggs, it might be safe to say that for purposes of regular ol’ cooking—not beakers-and-test-tubes turf—more acidity means less browning, and more alkalinity means more.