Baozi (Mantou) Dough

Skip to the recipe

The key to all your favorite dim sum classics is much easier than you think.

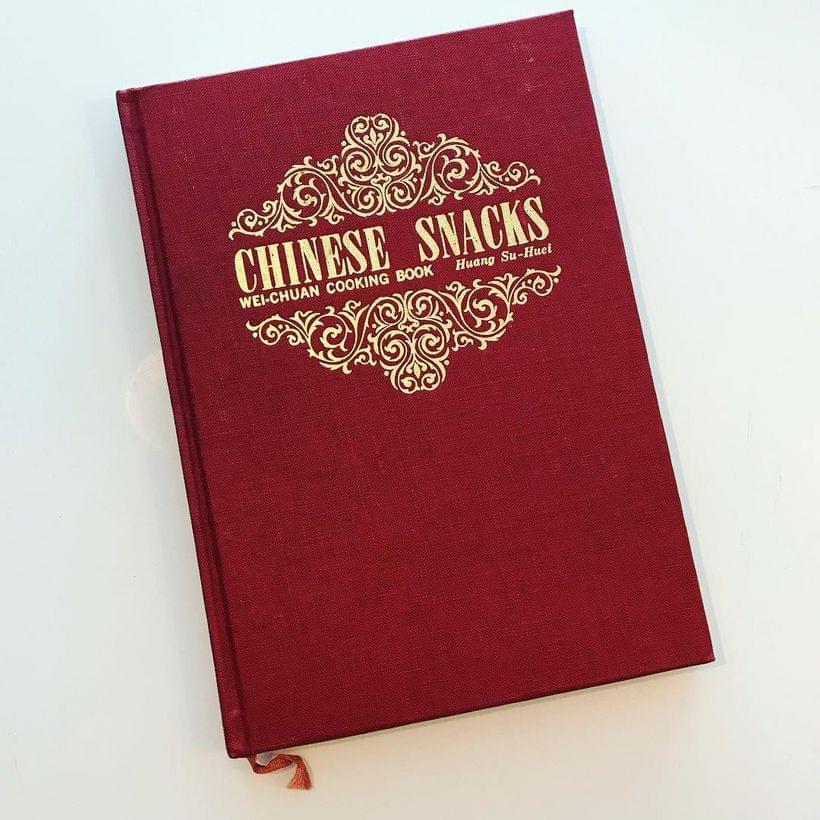

Let me begin this recipe with some crucial advice—not for this recipe, but for life. Beg, borrow, or steal a copy of Chinese Snacks by Huang Su-Huei, published by Wei-Chuan. It’s part of a set, the other half being Chinese Cuisine—which I only just managed to find and order from a used bookstore in Maryland.

This recipe isn’t from Chinese Snacks, which does contain several recipes for this kind of dough (including a sourdough one). No, I cobbled this one together myself. It isn’t far off from the go-to dough recipe in the book, though, mostly by nature of the simplicity of the dough itself: a pretty standard yeast-raised, oil-enriched affair, with the “oven spring,” so to speak, bolstered by a little baking soda.

The only thing that might feel a little out-of-place on this one is the cake flour, which gives these a finer texture than strictly all-purpose would. That also means a little less gluten formation, which—even though this is a dry, sturdy dough—might’ve made it a little trickier to work with. So, I use a little AP flour for, y’know, structural integrity.

Shaping

For gua bao, roll your pieces of dough into discs and fold them over a sheet of parchment to steam them, then fill them separately. For liu sha bao—my go-to for testing this recipe due to a macaron-induced surplus of frozen egg yolks—you just purse ’em up and flip them upside-down. For most baozi applications—well, the technique itself isn’t too tricky, but I don’t mind saying that I’m still getting the hang of it myself.

Steaming

So, the gist is that you sit your steamer baskets in a wok, fill the wok with water until it’s just touching the bottom of the baskets, and crank the heat up as high as it will go. I keep an electric kettle going to top up the water every so often.

My warning here is that this always beats the hell out of the seasoning on my wok, even if I start with a full pan of cold water and bring it up to heat gradually (never add water to a dry, screaming hot pan, unless you’re looking to remove your seasoning completely).

A flat-bottomed stainless pan would involve a lot more fussing with water levels and direct heat on the bottom of a wooden steamer basket, which isn’t the greatest idea ever. Something to raise the baskets off the bottom of the pan might work, but it means giving some of the steam a way to escape if the water level isn’t carefully managed. I have a skillet that the steamer baskets juuust barely sit atop, but it feels a little too precarious. I even thought about having a second wok for steaming purposes only, but I’m in an apartment kitchen, here—we’ve had to institute a “one in, one out” rule on pots and pans as it is.

Other than hoping to find a perfectly steamer-basket-sized stainless steel saucier one day, the only answer I’ve got for either of us is a can of Bar Keepers Friend to take off what’s left of the flaky seasoning and a couple new coats of oil after using your wok. I take a little comfort in the idea that a wok isn’t some overly precious pristine French-named dealie—a wok is here to work. But still, it’s a pain.

All that aside, this method works great. Just make sure your bao don’t come into contact with cold air at any point in the steaming, or they might deflate on you. Likewise, don’t yank them out of the steam as soon as they’re ready: I turn off the heat and leave them to cool a little over the residual steam, then remove the unopened basket and set it aside to cool a little further before opening it up.

Recipe: Mantou Dough

For bao of every shape and size.

Ingredients

-

250 G. Cake Flour

-

50 G. All-Purpose Flour

-

1 tsp. Instant Yeast

-

1 Tbsp. Sugar

-

1 Tbsp. Coconut Oil, but any neutral oil should work

-

1/8 tsp. Baking Soda

-

A Pinch Kosher Salt

-

160 G. Water, between 90–100°f

Instructions

Combine everything but the water in a large bowl, or in the bowl of a stand mixer fitted with a paddle bit. Mixing on low speed, or by hand, add water until dough comes together into a shaggy ball. Switch to a dough hook/spiral and knead on low–med speed for 5 min, or hand-knead for seven or eight minutes, until smooth.

Form into a ball and place into a clean, well-oiled bowl to rise for 1–1.5 hours, or until doubled in size.

Remove to surface lightly dusted with all-purpose flour and knead gently to deflate. Divide into uniformly sized pieces (probably eight, for most bao applications), roll each piece into a ball, and flatten with a small rolling pin (dusting with a small amount of flour as-needed to prevent sticking) and shape.

Cook in steamer baskets seated in a wok filled with boiling water for 15 minutes, without separating the baskets or otherwise exposing the dough to cool air. When done, turn off heat and allow bao to cool slightly inside the baskets before exposing to cool air, to help prevent collapse.